Theater and Possibility

Meet the Participants

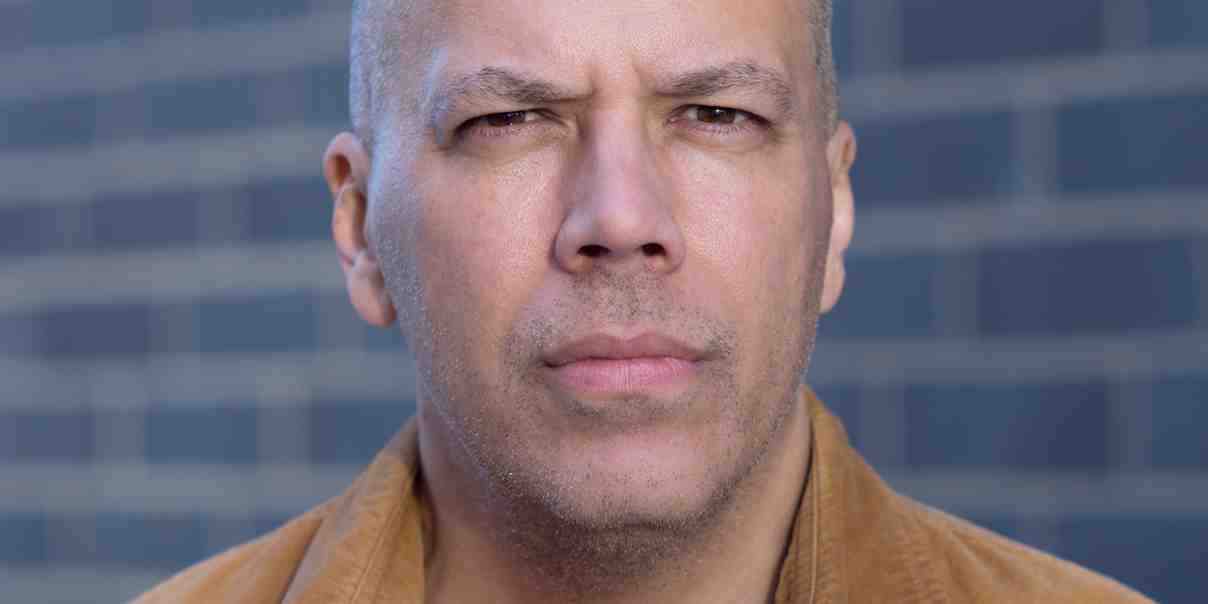

Jorge Ignacio Cortiñas (Writer, Director) plays include BIRD IN THE HAND (Fulcrum Theater, New York; New Theatre, Miami; NY Times Critics Pick), BLIND MOUTH SINGING (National Asian American Theater Company, New York; Teatro Vista, Chicago; NY Times Critics Pick), and SLEEPWALKERS (Alliance Theater, Atlanta; Area Stage, Miami; Carbonell Award for Best New Play). Awards include fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts; New York Foundation for the Arts (three years); Helen Merrill Award; Anschutz Distinguished Fellowship at Princeton University; and the Robert Chesley Award. His plays are published by Playscripts, Dramatic Publishing and TDR. Other works include a solo performance entitled BACKROOM (Whitney Museum of American Art in New York) and an interactive "play without a script" entitled PICK A CARD (GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco.) He is the founder of the Obie-winning Fulcrum Theater, a Usual Suspect at New York Theatre Workshop, and an alumnus of New Dramatists.

There’s that moment when I am sitting in my seat facing the empty stage and the lights begin to dim. That moment asks for our attention, it’s like the exhale before a close friend begins to share something important. Whatever the ferocious world has thrown at us today, we are now in a theater and a story is about to begin. I still myself; I try to be patient enough to receive the play.

New York is not an easy city to live in. It’s not just that the very architecture reminds me that the place where I live is run by people whose priorities do not often include the welfare of those I love the most. Because even if this was an equitable city, the logistics of eight million people living together would still be exhausting. Why then, after a day of avoiding the wet press of strangers on the subway platform, after dodging clumps of tourists on narrow sidewalks, should I seek out the impossibly tight seats that New York theaters are known for? (Have you noticed what cavernous Broadway houses and tiny downtown performance spaces have in common? Tight seats!) I could lock my apartment door, curl up with my laptop and stream an episode of some comforting serial. Instead, I squeeze myself into yet another cramped New York theater, strangers once again pressed in all around me. Why?

I’ve heard some refer to theater as a kind of townhall but the metaphor strikes me as imprecise. In a townhall it is our civic responsibility to speak, shout if that is what it takes to be heard. But we watch theater in relative silence so as not to disrupt the work of the actors. Hushing ourselves in this way may engender feelings of awe and that brings to mind another metaphor I sometimes hear friends invoke – theater as a kind of church service. Perhaps those friends had very different religious upbringings than I did. The church I grew up in was obsessively hierarchal, sexually repressed and read to us from the same book Sunday after Sunday. A healthy theater, by contrast, should feature a dizzying array of perspectives and challenge our familiar ways of thinking. The best theater cannot always be politically palatable and cannot be engineered by a college of cardinals. These metaphors fall short because theater should aim to exceed the narrow boundaries of our politics and our religions.

As I watch a play, I am aware of the audience members sitting on either side of me. If it is a good play, I am aware that we are all listening. In this polyglot city, it is unlikely that we are having the same reaction to what we are seeing and hearing. We may not even be having similar reactions. But we will be paying attention and we will be aware that we are paying attention together. Crucially, this awareness comes without us speaking to each other. Whatever we are experiencing, the play wants us to hold off on discussing it. The play wants us to be attentive without grasping for language. In the dark of the theater, we have entered a realm that sits just outside our attempt to definitively describe it. And the play asks us to linger in that realm – quietly, together – before we rush off to our post-theater drinks where we will debate what the play was about, assign it a label and rate it.

I love my brilliant friends and I love bourbon and I love talking about theater and I love punctuating my sentences by banging a lowball glass on a wooden bar. But I prefer the moments before we do that. I prefer the time we spend sitting quietly together in the realm of the sensual, the realm of emotion, the realm of the mysterious. We feel then that we are in the presence of something that, just for the duration of the performance, is alive. The autonomy of this living thing we call a play is a miracle. There was nothing on that stage before the lights dimmed and there will again be nothing on that stage after we have left the theater in search of an open bar – but right now, there is. That miracle, a miracle that happens every night somewhere in New York City, creates in us a feeling of potential.

Too often – in this city, and in others – the powerful curtail possibility in the lives of those with less power. Too often, the powerful ask the rest of us to believe that current social arrangements are immutable, fixed. But in the theater we are able to see that almost nothing is truly fixed. That feeling of potential when the lights are dimmed and we all lean in to listen? To be in the presence of that warm glow of potential is the reason I come to the theater. My fellow audience members, I want you to know that I can sense you sitting close to me in the dimness of the theater and that the potential we are feeling together is a feeling adjacent to hope.

Related Productions

Written by

Jorge Ignacio Cortiñas