The Give and Take Between Memory and Invention: "What Is Real Is Imagined"

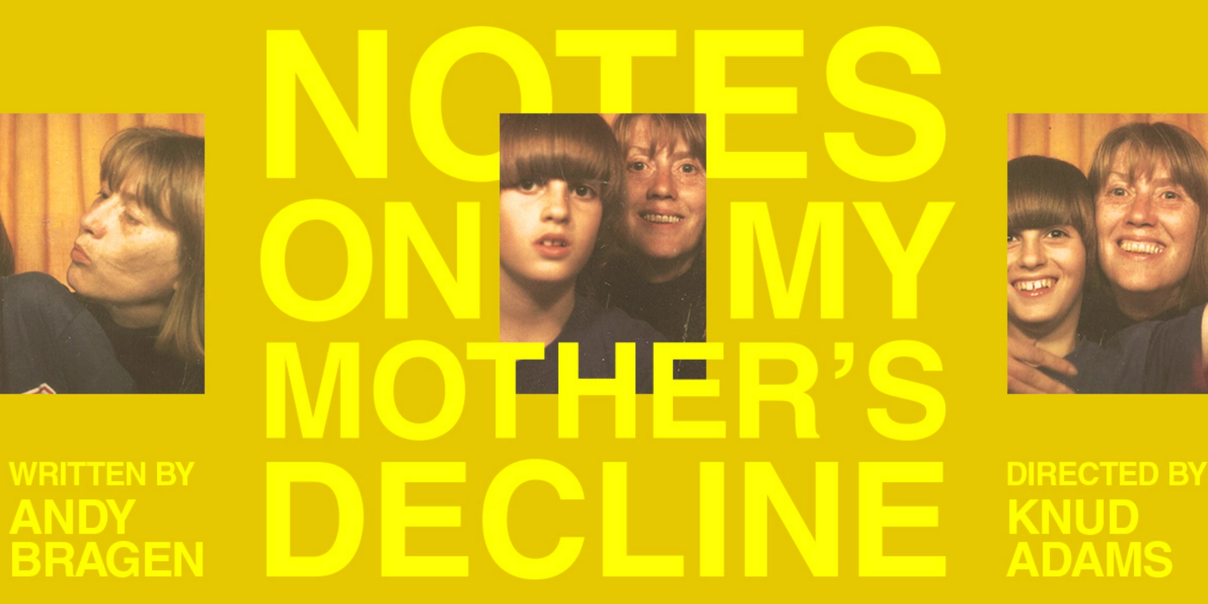

Notes on My Mother’s Decline playwright Andy Bragen has taught theatre and playwriting at Brown University, Franklin & Marshall College, Ohio State University and Sewanee: The University of the South. He currently teaches at Barnard College in New York City. Andy shares with us an essay by acclaimed Irish writer Colm Tóibín that he often has his students read and discuss:

“In my playwriting classes, I often distribute this essay at the beginning of the semester. It touches on the interplay between memory, and invention, and explores how language and rhythm can help connect these things. One of my teachers in graduate school, Erin Cressida Wilson, exhorted us to write both “more and less personally”, and this essay has helped me to understand how I might do that. My mother’s voice, and her language, her self as I remember her are central to Notes on My Mother’s Decline. These memories create a base, a grounding, for the structure of the play, the fictions of it. The play’s fiction may in fact lie in the structure, in the form that I found through revision and experimentation. Toibin writes: ‘The story has a shape, and that comes first, and then the story and its shape need substance and nourishment from the haunting past, clear memories or incidents suddenly remembered or invented, erased or enriched. Then the phrases and sentences begin, another day’s work.’”

- Andy Bragen

--

As night falls, I watch from the window as flashes from Tuskar Rock Lighthouse become visible. It does its two flashes and then stops as though to take a breath. Until I was 12 and my family stopped coming to this remote place on the coast of Ireland in the summer, I watched the lighthouse too, from a different window not far from here. Every day now as I walk down to the strand I pass the house we lived in then. Someone else is there now, but no matter what happens, the room that I can almost peer into from the lane remains my parents’ bedroom, with the iron bed and the cement floor. I suppose it must seem smaller now that I am bigger.

And the smell of clover in the field before the cliff is the same smell, although it must be different clover. Maybe the smell is similar and not the same, but because I am trying all day to dream that world of 1967 into existence, it is sometimes closer now than it ever was.

There is a farmers’ market in Enniscorthy town, 10 miles away, on Saturday mornings. Some of the pubs in the town have the same names and the same atmosphere they had when I was growing up, but almost everything else has changed. Every shop that I remember has gone. Some of the buildings in the center are empty; some have different uses. It would be easy to exaggerate, to say that the town is more real as I remember it than it is now. Clearly, that is not true. What’s real is there now; the rest is memory, history and it hardly matters. This is a poor fact and will remain one whatever I do and whatever I write.

The world that fiction comes from is fragile. It melts into insignificance against the universe of what is clear and visible and known. It persists because it is based on the power of cadence and rhythm in language and these are mysterious and hard to defeat and keep in their place. The difference between fact and fiction is like the difference between land and water.

What occurs as I walk in the town now is nothing much. It is all strange and distant, as well as oddly familiar. What happens, however, when I remember my mother, wearing a red coat, leaving our house in the town on a morning in the winter of 1968, going to work, walking along John Street, Court Street, down Friary Hill, along Friary Place and then across the bottom of Castle Hill toward Slaney Place and across the bridge into Templeshannon, is powerful and compelling. It brings with it a sort of music and a strange need. A need to write down what is happening in her mind and to give that writing a rhythm and a sound that will come from the nervous system rather than the mind, and will, ideally, resonate within the nervous system of anyone who reads it.

I don’t know what she thought, of course, so I have to imagine. In doing so, I use certain and uncertain facts, but I add to the person I remember or have invented. Also, I take things away. This is a slow process and it is not simple. I give my mother a singing voice, for example, which she did not have. The shape of the story requires that she have a singing voice; it is the shape of the story rather than the shape of life that dictates what is added and excised.

But the singing voice is a mere detail in a large texture of a self that gradually comes alive — enough to seem wholly invented and fully imagined, although based on what was once real.

All the rooms, however, are really real, as real as they once were. The rooms in our house in the town must be there still, but it is how they were in the late 1960s that matters to me now and that I can reconstruct in the sort of detail which gives me satisfaction and makes me forget myself. Conjuring them requires me to work with the sentences and their shape. The more I remember accurately, the more easily phrases come and the more accurate they seem when I reread them at night and again in the morning.

I have been writing about writers and their families so it is strange that the idea of rights versus responsibilities does not preoccupy me. I feel that I have only rights, and that my sole responsibility is to the reader, and is to make things work for someone I will never meet. I feel just fine about ignoring or bypassing the rights of people I have known and loved to be rendered faithfully, or to be left in peace, and out of novels. It is odd that the right these people have to be left alone, not transformed, seems so ludicrous.

Within a few months of marrying, Thomas Mann wrote a story suggesting that his wife had had an incestuous relationship with her twin brother. Samuel Beckett, in his first book of stories, used a letter from a dead cousin, thus causing offense to her family. Brian Moore’s father, who was a doctor, worked tirelessly during the bombing of Belfast in 1941; in his novel “The Emperor of Ice Cream,” Moore has the father, who is clearly based on his own father, fleeing Belfast for the safety of Dublin during the air raids.

No one suggests that Mann or Beckett or Moore was an especially bad person. Indeed, all three were known for their courtesy and much loved by those close to them and by readers. But when it came to the moment when they were putting their stories together, working out the details, mixing memory and desire, they had no qualms, no problems about appropriating what they pleased. They used what they needed; they changed what they used. Their soft hearts became stony.

If I tried to write about a lighthouse and used one that I had never seen and did not know, it would show in the sentences. Nothing would work; it would have no resonance for me, or for anyone else. If I made up a mother and put her in another town, a town I had never seen, I wouldn’t bother working at all. I would turn to drink, or just sit at home, or run for election. If I had to stick to the facts, the bare truth of things, that would be no use either. It would be thin and strange, as yesterday seems thin and strange, or indeed today.

The story has a shape, and that comes first, and then the story and its shape need substance and nourishment from the haunting past, clear memories or incidents suddenly remembered or invented, erased or enriched. Then the phrases and sentences begin, another day’s work. And if I am lucky, what comes into shape will, despite all the fragility and all the unease, seem more real and more true, be more affecting and enduring, than the news today, or the facts of the case, or the beams of Tuskar Rock Lighthouse as night falls and the real darkness comes.

Related Productions

Written by

Colm Tóibín

Curated by

Andy Bragen